What Cathedrals and the Grail Literature Can Teach Us About Community

There isn’t just one ‘Grail’ story, it was a story concept addressed by many authors over decades. A few of the more significant examples would include:

The Perceval, le Conte du Graal (The Story of the Grail) by Chrétien de Troyes (c. 1190). In this long but incomplete poem, the grail was a simple bowl without the magical holiness it acquired in later works.

Joseph of Arimathea by Robert de Boron (c.1200). Robert tells the story of Joseph of Arimathea acquiring the chalice of the Last Supper to collect Christ's blood upon his removal from the cross. Joseph is thrown in prison, where Christ visits him and explains the mysteries of the blessed cup. Upon his release, Joseph gathers his in-laws and other followers and travels to the west, founding a dynasty of Grail keepers which eventually includes Perceval.

Perceval by Wolfram von Eschenbach (c. 1200). Eschenbach claims that the Grail was a stone called Lapis exillis, which in alchemy is the name of the philosopher’s stone. Eschenbach’s story follows the journey of Perceval as he seeks to become a knight and discovers his destiny as the Grail Knight. Along the way, Perceval encounters various trials, including encounters with knights, maidens, and mystical beings, ultimately leading to his attainment of the Holy Grail and spiritual enlightenment.

The "Morte d'Arthur" (“Death of Arthur) by Sir Thomas Malory (15th century). A compilation of various Arthurian legends and stories, focusing primarily on the life and reign of King Arthur, his knights of the Round Table, and the quest for the Holy Grail.

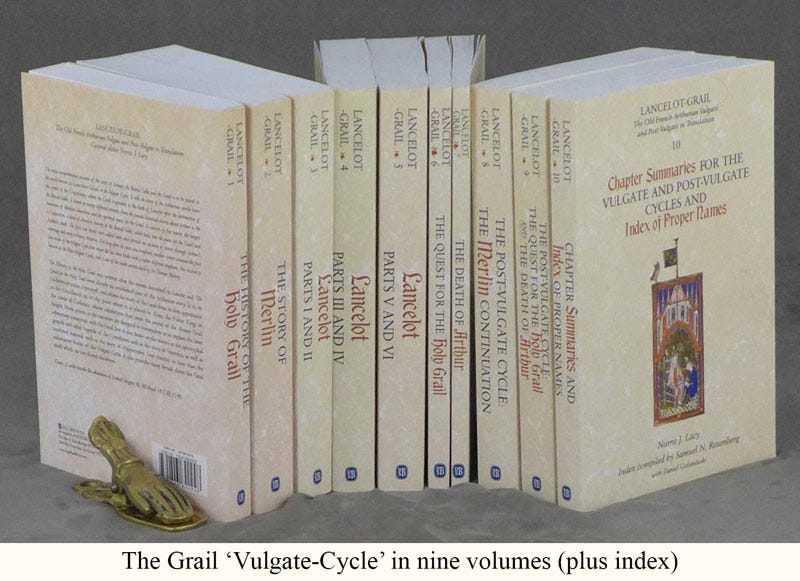

The so-called Vulgate Cycle and the Post Vulgate Cycle (1210-1240): Stories of Arthur, the Round Table, romances of chivalric adventure, and the spiritual quest for the Grail in nine volumes. Some of it is traditionally attributed to Walter Map, the rest is anonymous. Modern scholarship questions Walter Map’s authorship, making this large body of literature entirely anonymous.

This list of the Grail literature from that era is a far from complete.

More or less simultaneously, we have an eruption of cathedral building during the 13th and 14th centuries — hundreds of them. This period witnessed the construction of iconic cathedrals such as Notre-Dame de Paris, Chartres Cathedral, Salisbury Cathedral, and Amiens Cathedral, among others. While some cathedrals were completed within a few decades, many took several generations or even centuries to finish.

Although we know the names of some cathedral designers and builders from surviving business documents, many cathedral builders chose to remain anonymous for various reasons. Some may have viewed their work as a form of devotion to God rather than seeking personal recognition. Additionally, guild traditions and the hierarchical structure of medieval society may have dictated that credit for cathedral construction be attributed to the institution or the community rather than individual builders.

A major reason that humanity has survived and thrived is that we banded together into tribes. Communities. By ourselves, individually, survival prospects are grim. But by banding together, humanity has become unstoppable.

At the same time, it is individual insight and industry that advances the well-being of the community. Someone realized the potential of fire. Someone figured out how to make a button. Someone figured out the plow. To be sure it was certainly a serial effort – someone had the initial spark of an idea, the next realized how to improve it, and so on. But ideas occur to individuals (albeit sometimes to more than one person at the same time). Meanwhile, communities that encourage individual innovation and industry do better than those that don’t.

So we have an ongoing tension between the well-being of the individual and the well-being of the community as a whole. Generally their interests coincide, but not always.

The point I’d like to make is that it would seem that 13th-century Europe significantly differed from our own in this respect: we’re obsessed with ‘creating a name’ for ourselves, while in the 13th century, this wasn’t so important. Cathedral builders would undertake construction, knowing that it would be their grandchildren who completed it. It wasn’t about personal glory, it was about devotion to God as they understood Her and benefitting their community, whether they received personal credit or not. Nowadays, in movie credits, the assistant dog groomer has to be listed by name.

Likewise with the Grail Vulgate Cycle — an enormous body of literature in which being credited by name apparently wasn’t important. Instead, these authors were inspired by the Grail legend and surrounding stories, wanted to contribute, and didn’t care if they received personal credit or not.

Pendulums swing back and forth, including social ones. We live in an era in which the individual is hyper-emphasized, and our sense of community has suffered. And not just our ‘sense of community’, but community itself has suffered.

Perhaps we can be on the cutting edge of social betterment by rebuilding, by nurturing community from the ground up. From the grass roots. This is not something that can happen by a new law, or corporate campaign. It has to come from individuals recommitting to the welfare of their community — both local and global.

After all, we individuals are all in this together.

William Zeitler

Thanks for reading GrailHeart! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Did you enjoy this article? Consider forwarding it to a friend!

Would you like to contribute to the conversation?